11 Problems 3

Week 6

11.1 Vector product

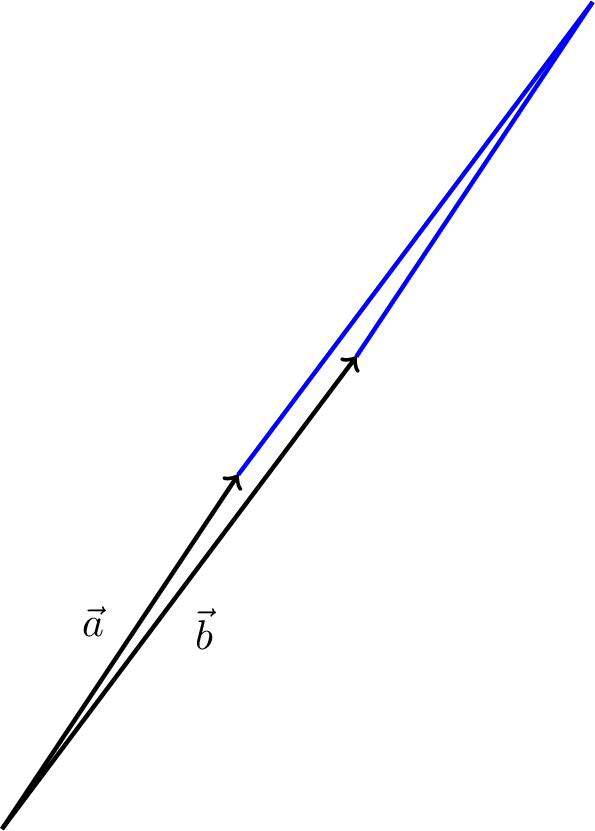

Find the vector product of \(\vec{a} \times \vec{b}\) where \[ \vec{a} = 2\hat{\imath} + 3\hat{\jmath} \] \[ \vec{b} = 3\hat{\imath} + 4\hat{\jmath} \]

Draw a sketch to check your answer – does the magnitude of the vector correspond to the area you expect, and is it in the direction you expect?

We need to find the determinant of the following \(3 \times 3\) matrix. \[ \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\imath} & \hat{\jmath} & \hat{k} \\ 2 & 3 & 0 \\ 3 & 4 & 0 \end{vmatrix} \] Using Equation 8.1 we get \[ \vec{a} \times \vec{b} = {\color{green} +(3 \times 0 - 4 \times 0) \hat{\imath}} {\color{blue} -(2 \times 0 - 3 \times 0) \hat{\jmath}} {\color{red} +(2 \times 4 - 3 \times 3) \hat{k}} \] \[ \vec{a} \times \vec{b} = - \hat{k} \]

11.2 Lorentz force

The force on a particle of charge \(q\) moving with velocity \(\vec{v}\) due to an electric field \(\vec{E}\) and a magnetic field \(\vec{B}\) is given by the Lorentz force, defined as follows. \[ \vec{F} = q (\vec{E} + \vec{v} \times \vec{B}). \]

A particle of charge \(+1\) coulomb is moving with velocity \(\vec{v}\) in an electric field \(\vec{E}\) and magnetic field \(\vec{B}\).

Calculate the force on the particle if \[ \vec{v} = 8.3 \hat{\imath} + 5.6 \hat{\jmath} \text{ m s}^{-1} \] \[ \vec{E} = \vec{0} \text{ V m}^{-1} \] \[ \vec{B} = 1.7\hat{\imath} + 5.0\hat{\jmath} \text{ T}\]

Is any work being done on the particle by the Lorentz force in this case?

Calculate the force on the particle if \[ \vec{v} = −9\hat{\imath} + 6\hat{\jmath} − 3\hat{k} \text{ m s}^{-1} \] \[ \vec{E} = 6\hat{\imath} − 4\hat{\jmath} + 2\hat{k} \text{ V m}^{-1} \] \[ \vec{B} = 3\hat{\imath} − 2\hat{\jmath} + \hat{k} \text{ T}\]

\[ \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\imath} & \hat{\jmath} & \hat{k} \\ 8.3 & 5.6 & 0 \\ 1.7 & 5.0 & 0 \end{vmatrix} = (0)\hat{\imath} - (0)\hat{\jmath} + (8.3 \times 5.0 - 1.7 \times 5.6)\hat{k} \] \[ = 32 \hat{k} \text{ N} \]

No work is being done because the force is perpendicular to the velocity.

Let’s first calculate \(\vec{v} \times \vec{B}\) which is given by \[ \vec{v} \times \vec{B} = \begin{vmatrix} \hat{\imath} & \hat{\jmath} & \hat{k} \\ -9 & 6 & -3 \\ 3 & -2 & 1 \end{vmatrix}\] \[ = (6 - 6)\hat{\imath} - (-9 + 9)\hat{\jmath} + (18 - 18)\hat{k} \] \[ = \vec{0} \] because \(\vec{v}\) is parallel to \(\vec{B}\). Therefore, \[ \vec{F} = q ( \vec{E} + \vec{0} ) = 6\hat{\imath} − 4\hat{\jmath} + 2\hat{k} \text{ N} \] All three vectors parallel, solution parallel to \(\vec{E}\).

11.3 Circular motion in a synchrotron – angular SUVAT

Synchrotrons are used to generate high intensity X-ray beams. The Diamond light source at Harwell in Oxfordshire is one of the most powerful X-ray sources available for physics research. At Diamond, electrons are first accelerated in a linear accelerator and then injected into a synchrotron ring where they are further accelerated (by a constant angular acceleration α) up to their final speed, which is a substantial fraction of the speed of light.

Suppose the electrons are travelling with a speed \(v\) when they first enter the synchrotron ring which has a radius \(R\). This means they have an initial angular speed \(\omega_0 = v/R\) (measured in rad s\(^{-1}\)) and are subjected to a constant angular acceleration \(\alpha\) measured in rad s\(^{-2}\), until they reach their final speed. You may also assume that the initial angle that the electrons enter the ring \(\phi_0 = 0\) rad. You should ignore relativistic effects.

- Write down an equation describing the angular velocity \(\omega\) of an electron as a function of time since its injection.

- By integration, find an equation describing the angular position \(\phi\) (in radians) of the electron as a function of time.

- Using the result of the previous part, find the total distance (in m) that the electron will move around the synchrotron ring as a function of time.

We start by constructing an algebraic expression describing the angular velocity increasing linearly as a function of time, i.e., with a constant angular acceleration \(\alpha\) \[ \omega(t) = \omega_0 + \alpha t \]

By writing the angular velocity as \(d\phi/dt\), we can find an expression for the angular position \(\phi\) as a function of time. \[ \phi = \int_{t'=0}^{t'=t} \omega(t') dt' \] \[ = \int_{t'=0}^{t'=t} (\omega_0 + \alpha t') dt' \] \[ = \omega_0 t + \frac{1}{2} \alpha t^2 \]

The distance travelled \(s(t)\) around the ring is the angular coordinate multiplied by the radius \(R\) of the ring. So \[ s (t) = R\phi(t) = R \left( \omega_0 t + \frac{1}{2} \alpha t^2 \right) \]

11.4 Moment of inertia of a cylinder

Note: I have changed the wording of this question a little bit after feedback from the problems class in an attempt to make it clearer. Please get in touch if anything isn’t clear; I am happy to discuss it with you.

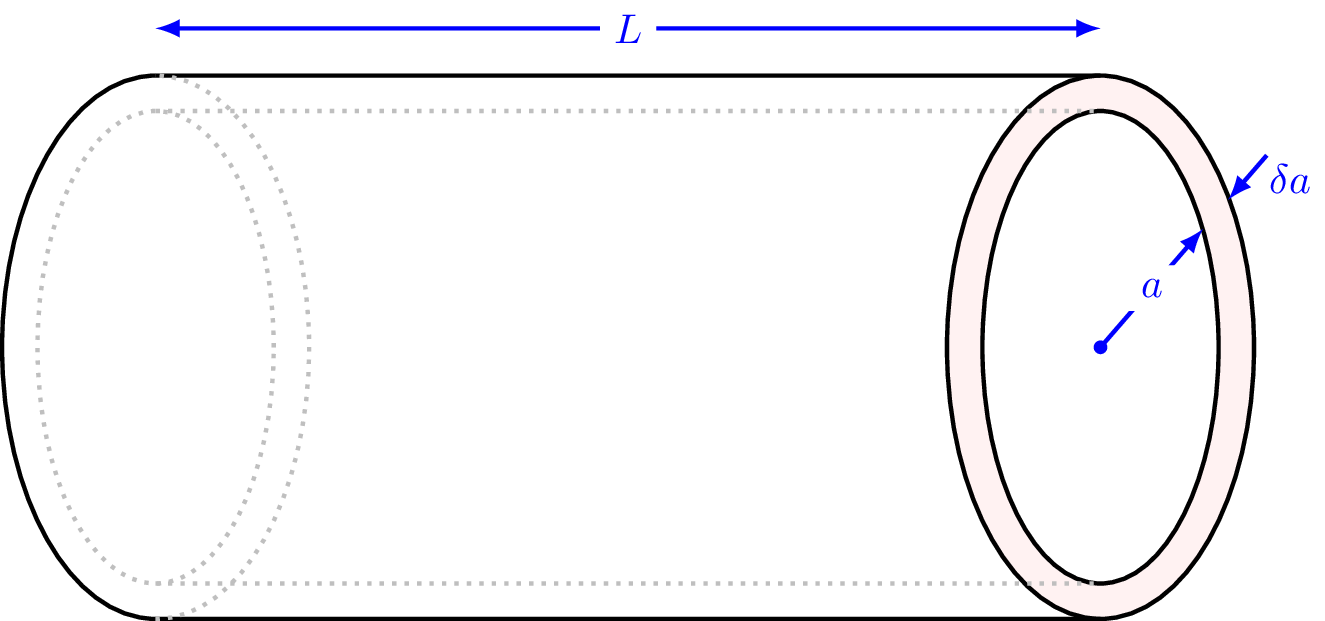

Consider a thin cylindrical shell of density \(\rho\), length \(L\), radius \(a\), and thickness \(\delta a\), where \(\delta a\) is small.

Show that the mass of the shell is given by \[ \delta m = \rho L 2\pi a \delta a + \underbrace{\rho L \pi (\delta a)^2}_{\text{\color{blue} we can ignore this term (see below)}} \] and its moment of inertia about the axis of the cylinder is given by \[ \delta I = \rho L 2\pi a^3 \delta a + \underbrace{\rho L \pi a^2 (\delta a)^2}_{\text{\color{blue} we can ignore this term (see below)}} \]

Hence, in the limit as \(\delta a \to 0\), \[ \frac{dI}{da} = \rho L 2\pi a^3 \]

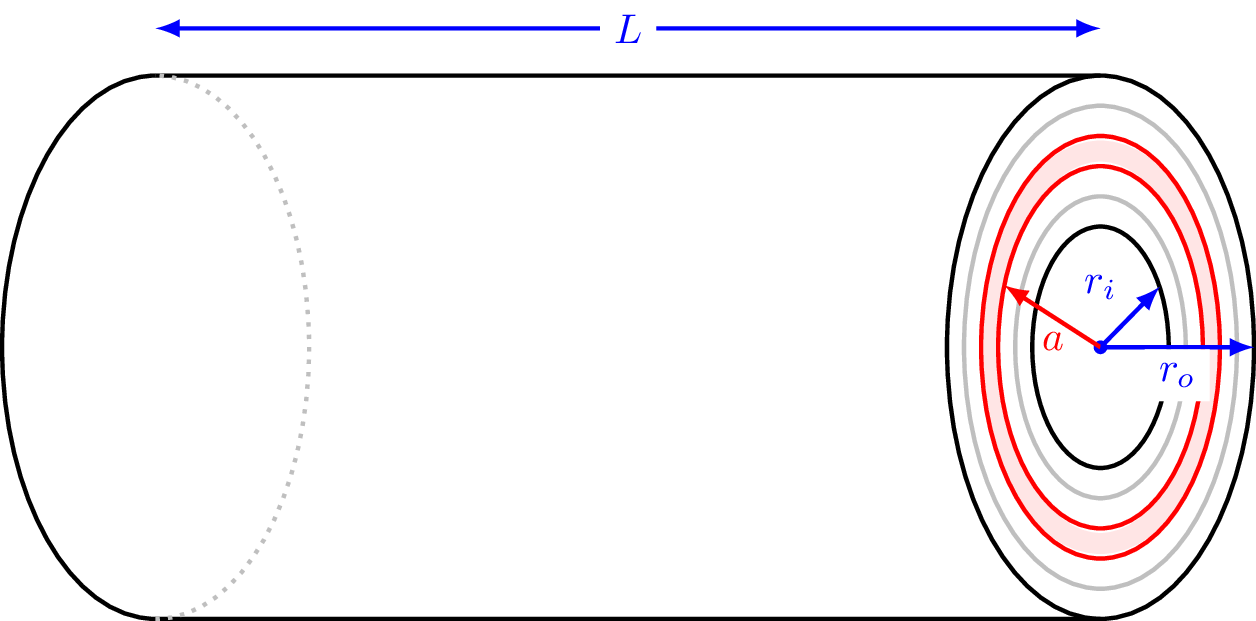

The moment of inertia about the axis of a uniform, thick cylindrical tube of density \(\rho\), length \(L\), inner radius \(r_i\) and outer radius \(r_o\) can be calculated by considering the tube as the sum of many thin cylindrical shells. Explain, with the aid of a diagram, why the moment of inertia of the tube is given by \[ I = \int_{I_i}^{I_o} dI = \int_{a = r_i}^{a = r_o} \frac{dI}{da} da \] and hence show that \[ I = \frac{\pi\rho L}{2} (r_o^4 - r_i^4) \]

Find an expression for \(\rho\) in terms of \(M\), \(r_i\), \(r_o\), and \(L\), and show that \[ I = \frac{1}{2} M (r_i^2 + r_o^2)\]

Write down expressions for the linear and rotational kinetic energy of such a cylinder when the centre of mass has a speed of \(v_\text{com}\). Assume the cylinder is rolling and not slipping.

Hint: you can write \(v_\text{com} = \omega r_o\).

Such a hollow cylinder is released at the top of a slope and rolls down the slope, under gravity, without slipping. Show that the speed of the centre of mass after the cylinder has dropped by a vertical distance \(h\) is given by \[ v_\text{com} = \sqrt{\frac{4gh}{3+\left(\frac{r_i}{r_o}\right)^2}} \]

A hollow cylinder of mass 1 kg with inner radius 5 cm and outer radius 8 cm is rolling along the ground; the centre of mass has a speed of \(1.6 \text{ m s}^{-1}\).

- What is the angular velocity of the cylinder?

- What is the linear kinetic energy of the cylinder?

- What is the rotational kinetic energy of the cylinder?

The mass of the thin shell, shown in Figure 11.1, is given by the product of its circumference, thickness, length, and density \[ \delta m = (\pi (a + \delta a)^2 - \pi a^2) \times (L) \times (\rho) \] \[ = \rho L 2 \pi a \delta a + \rho L \pi (\delta a)^2 \] which is the answer required.

In lecture we noted that the moment of inertia of a hoop is given by \[ \delta I = a^2 \delta m \] because all of the mass is a distance \(a\) from the rotation axis. Hence \[ \delta I = 2\pi a^3 \rho L \delta a + \rho L \pi a^2 (\delta a)^2 \]

Rearranging this gives \[ \frac{\delta I}{\delta a} = 2\pi a^3 \rho L + \rho L \pi a^2 \delta a \] Taking limit at \(\delta a \to 0\) gives \[ \frac{dI}{da} = 2\pi a^3 \rho L \]

Note: in future problems and lecture courses you will typically just write down the answer ignoring the terms of order \((\delta a)^2\), knowing that these will disappear in the limit as \(\delta a \to 0\).

We can build up a thick cylinder out of individual, thin cylindrical shells, as shown in Figure 11.2.

We need to add up all of the moments of inertia of the individual shells to get the total moment of inertia of the thick cylinder. This is given by

\[ I = \int_{I_i}^{I_o} dI = \int_{a = r_i}^{a = r_o} \frac{dI}{da} da \] \[ I = 2\pi \rho L \int_{a = r_i}^{a = r_o} a^3 da \] \[ I = 2\pi \rho L \left[ \frac{1}{4} a^4 \right]_{r_i}^{r_o} \] \[ I = \frac{\pi\rho L}{2} (r_o^4 - r_i^4) \]

The total mass of the cylinder is equal to its density times its volume. \[ M = \rho L \pi (r_o^2 - r_i^2) \] which we can rearrange for the density, \(\rho\), as follows \[ \rho = \frac{M}{L \pi (r_o^2 - r_i^2)} \] Hence \[ I = \frac{\pi L}{2} \frac{M}{L \pi (r_o^2 - r_i^2)} (r_o^4 - r_i^4) \] \[ I = \frac{1}{2} M \frac{(r_o^2 - r_i^2)(r_o^2 + r_i^2)}{(r_o^2 - r_i^2)} \] \[ I = \frac{1}{2} M (r_i^2 + r_o^2) \]

The diagram is similar to the example we went through in the last lecture, and is shown in Figure 8.14.

Linear kinetic energy is given by \[ \text{Linear KE} = \frac{1}{2} M v_\text{com}^2 \] Rotational kinetic energy is given by \[ \text{Rotational KE} = \frac{1}{2} I \omega^2 \] where \(\omega\) is the angular velocity of the cylinder. Since the cylinder is not slipping \(\omega = v_\text{com}/r_o\). \[ \text{Rotational KE} = \frac{1}{2} I \left( \frac{v_\text{com}}{r_o} \right)^2 = \frac{1}{4} M v_\text{com}^2 \left( 1 + \frac{r_i^2}{r_o^2} \right) \]

As the cylinder rolls down the slope under gravity, the change in its gravitational PE is equal to the increase in KE. From the previous part, the total KE is \[ \text{Total KE} = \frac{1}{4} M v_\text{com} \left( 3 + \frac{r_i^2}{r_o^2} \right) \] while the increase in gravitational PE is \(Mgh\). Setting these two energy changes equal to each other gives, \[ \frac{1}{4} v_\text{com} \left( 3 + \frac{r_i^2}{r_o^2} \right) = gh \] \[ v_\text{com} = \sqrt{\frac{4gh}{3+\left(\frac{r_i}{r_o}\right)^2}} \] as required.

- \[ \omega = \frac{v_\text{com}}{r_o} = 20 \text{ rad s}^{-1} \]

- \[ \text{Linear KE} = 1.28 \text{ J} \]

- \[ \text{Rotational KE} = 0.64 \left( 1 + \frac{25}{64} \right) = 0.89 \text{ J} \]